BUNYORO-KITARA MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

AMAKONDERE

Every year the Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom celebrates the coronation anniversary of the king, known as Empango. During the festivities, amakondere are played for the royal processions and also to accompany dances. There are four groups of amakondere players, and they play one after the other: the Kibaire Group, the Bugambe Group, the Kibiro Group, and the Alleluya Group. The first three groups comprise players who performed before the abolition of kingdoms.

The Amakondere dance is not an ordinary dance, but a royal orchestra consisting of a dozen elderly men. A horn-shaped, wooden side-blown trumpet is the main instrument in the production of royal court music for the Bunyoro and Toro kingdoms aristocracy. It is a major activity meant to entertain the Omukama (King).

The trumpets which are cylindrical, with one end wider have a sooty tinge are of different lengths and sizes. To produce melody from the trumpets, the Abakondere (trumpeters) draw breath from the depth of their lungs and press their lips hard on the wood. Their costumes consist of bark-cloth, fastened in a knot over the right hand shoulder.

Judging from the expression on the trumpeters faces, blowing the Amakondere is strenuous. It is for this reason that a reserve force of abakondere wait to take over when one gets tired.

A rich fusion of tunes and pitches is derived as each trumpet supplies a single musical note accompanied by the reverberations of drums (empango).

Yet for all its connection to royalty, the Amakondere trumpet has its roots in a vegetable called ebyara, which belongs to the gourd and pumpkin family. They are long, hard-skinned, climbing plants that exclusively grow in Kibiro on the shores of Lake Mwitazinge(Albert), Hoima district.

Legend has it that ebyara made their way into Bunyoro from the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.

To curve the Amakondere trumpets, the marrow of ebyara is removed to create a hollow structure.

Amakondere is associated with jubilation. Dancing to the Amakondere is called Okuguruka Amakondere. While the Amakondere is not performed during war, famine or when any calamity has befallen the Omukama, he may ignore the norm if he wishes.

The Omukama’s subjects also dance to Amakondere when an important person visits. It is a sign of respect that is deeply rooted in the Bunyoro-Toro way of life.

The Amakondere orchestra does not follow musical solfas. Instead, the tunes are derived mainly from folklore and praise the king.

Some of the orchestra tunes include entale, kigambo kyomujwigaa, which is translated as as, The King’s word is like a lion. When he roars, every soul has to fear.

The Amakondere choreography involves dancing in twos, side by side. The dancers alternately lift one foot in forward motion. The mens arms are raised and positioned as if holding an invisible spear with a shield. The lips are mute while the orchestra rumbles. The women wear suuka(Omwenagiro) while the men wear kanzus. The Amakondere are similar to the Agwara, a wooden trumpet in West Nile.

The Abakondere are selected from specific clans because blowing the Amakondere trumpets should not be done by anyone.

While dancing to the Amakondere orchestra is open to everybody, it cannot be performed without royal permission.

Amakondere songs include ‘Irambi (a slow royal dancing style of Bunyoro), ‘Ennumi[Bull], ‘Ruyanga [An Adamant Person], ‘Ichuma lya luswata’ [Spear of Person called Luswata] and ‘Kigambo k’yentale [Word of the lion]

The Different Sounds Types of Amakondere

huririza(Listen) to Amakondere songs

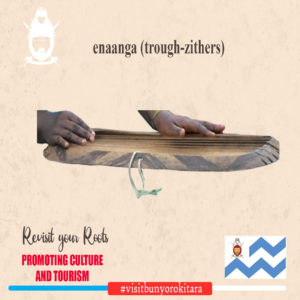

ENAANGA

The “enaanga” – is a type of zither that is composed of two main parts: the first part is called the “kitara” and consists of the wooden base-frame of the “naanga” zither. The frame is a shallow wooden-trough with “teeth” at the two convex opposite ends through which to run the strings. The trough is carved from the wood of the Nkukuuru tree [Euphorbia Candelabra]. The second part of the Naanga is a single cord made of sinews [ebinywa] from the tendons of a bull. This thin cord is strung over the open upper side of the trough, then through the teeth at each end of the zither frame, until it makes a six-stringed instrument. The naanga (zither) is played by plucking or strumming with the fingers.

The only other bits required on the properly assembled “Enaanga” are wooden fasteners – small wooden pegs, each about 2 inches long, that are used to tune the zither by tightening or loosening the cord at specific points between the teeth on either side of the frame.

In past times the strings used on the “nanga” were made of the tendon sinews from an old bull. Lately, however, the only cords available for stringing the “nanga” are made of sisal or plastic. The nanga that is strung with sisal or plastic doesn’t sound as good as the nanga strung with bull-sinew. Sinew is available to use, but sisal and plastic are found everywhere these days and are cheaper to obtain.

Enaanga is a trough-zither, and there are several types of them in Uganda. It may be impossible to identify them with certainty. For example, Mbabi-Katana (interview, Hoima, 10 April 2009) maintained that the enaanga of Bunyoro was the same as that of the Bakiga of southern Uganda. By contrast, Muhuruzi (interview, Hoima, 19 May 2009) asserted that the enaanga was a gourd trough with strings. Tigulyera (interview, Masindi, 22 May 2009) agreed that gourd troughs were sometimes used to make the enaanga. However, the photograph by Trowel and Wachsmann (Figure 5) indicates that the enaanga is wooden. Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 390) state that a gourd may be fixed to the trough to ‘reinforce the sound’. This might be the reason why some respondents told me that they are made from gourds. It should be noted that the Baganda people of central Uganda have an instrument called the ennanga (Trowel and Wachsmann 1953: 412), which is not a zither but a bow harp like the adungu of the Acholi people of northern Uganda or the adeudeu of the Itesot people of eastern Uganda. Nyindo

Nyindo and Owarutale (interview, Hoima, 9 April 2009) agreed that enaanga music was performed by the Bahuma people, and also the palace dwellers. According to Nyindo and Owarutale, the Bahuma (usually mistakenly thought to be the people of Ankole in western Uganda), who were predominantly cattle keepers, played the enaanga both outside and inside the palace. Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 390) state that in Bunyoro’ only women of the aristocracy’ played the enaanga unlike among the Bakiga people of southern Uganda, where it is an instrument for the commoners.’ Nyindo and Owarutale stated that in the palace the enaanga was also played by the king’s wives and the children who resided there. This information is confirmed by Wachsmann recordings from Bunyoro whose metadata mentions the king’s wife ( Omugo) as a performer of enaanga.

In my study, the Wachsmann archival recordings were useful in providing me with further information about enaanga music, especially its timbre, playing style and the lyrics of the songs. I listened to tracks such as ‘Ikangaine ya kyebambe’ (may be ‘Ihikangaine za Kyebambe’, which means the [cows] of Kyebambe have met each other), ‘Enanga ngaju ya omukama and ‘Mujuma ya Mugenyi (should be ‘Bijuma bya Mugenyi, which means fruits of Mugenyi) to deduce the following information.

Enaanga Songs

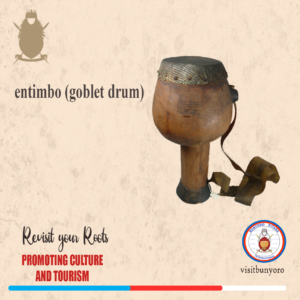

ENTIMBO

This percussion instrument is a traditional drum with its head made of cow hide or reptile skin nailed to a wooden sound body. The entimbo drums are among the important drums in the kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. The former king of Bunyoro-Kitara Rukirabasaija Tito Gafabusa Winyi, in a speech recorded by Hugh Tracey (1950), mentions the entimbo drums as major musical instruments of Bunyoro. Nyakatura (1947: 257) illustrates this when he describes the coronation ceremony of Bunyoro in which Omutimbo hands over to the king an ancient entimbo called Mutengesa. Also, the entimbo drums are listed among the items considered as the regalia of Bunyoro-Kitara.

The abatimbo songs are sung by the players of the entimbo drums called the abatimbo (singular: omutimbo—also a title of the player

At all times there was a group of the abatimbo performers in the palace, ready to fulfil their duties (Muhuruzi Isoke, the custodian of the royal drums, interview, Hoima, 11 June 2008). According to Omutimbo Kasiita, player of the entimbo drum (interview, Hoima, 18 May 2009), one of the kings settled the abatimbo near the palace so that they could provide their services whenever required.

In the palace, the entimbo drums are played when the king is walking, during the royal processions and wherever he is. Nyakatura (1947: 257) points out that ‘It is the drum that points to the direction where the king is going.’ K. W. (1937: 295) explains that during the coronation the king is handed an entimbo drum to signify: ‘Whenever the people hear the sound of this small drum they at once know that the Mukama [king] is roaming about in his enclosure.’ During the 2008 and 2009 coronation anniversary celebrations, I observed that the entimbo drums accompanied the king whenever he officially walked around and during his processions to the place called orugo, which is within the palace. Kasiita (interview, Hoima, 18 May 2009) and Emmanuel Mugenyi (interview, Hoima, 26 April 2009), the current abatimbo, asserted that they always sit near the king on official occasions and play briefly when the king makes an important point. Muhuruzi Isoke (interview, Hoima, 10 June 2008) asserted that they are supposed to play (together with the players of enseegu instruments) when the king has gone to bed, so as to soothe him to sleep, and at 6:00 am near the king’s bedroom to wake him up. The music played contains aesthetic properties that either soothe the king to sleep or awaken him. The current abatimbo admitted that they do not know the songs for soothing the king to sleep or waking him up. I believe that the entimbo music that was recorded by Wachsmann and Tracey may help in reviving this tradition.

Goines (1972: 48) states that ‘Music functions as an historical device, as a means through which current events are recounted, and as an educational vehicle.’ Important information is kept in music and is retrieved and passed on through music. For example, I learnt more and gained further understanding about the history and culture of Bunyoro through the study and analysis of the royal music. Tracey (1950) recorded a song the abatimbo used to sing: they recited words that praised [ebikubyo] and also related important historical events from Bunyoro’s history. Muhuruzi (interview, Hoima, 10 June 2008) confirmed that the abatimbo recitatives were composed from special events or occurrences in the past. The princesses (daughters of the former King Winyi) asked me to retrieve more songs from archives abroad that were sung by Nyakayonga (a renowned entimbo drum player), because his songs contained historical information about their father.

Therefore, the abatimbo played a role in keeping, retrieving and communicating information. The abatimbo I interacted with admitted that they cannot recite as they play because they have not yet learnt how to do it. Archival recordings may be useful in teaching the abatimbo how to compose and sing praise and historical songs. This can be achieved through perceptive listening to the archival entimbo songs, and analysing their styles and the messages they deliver. Then current and important events of Bunyoro may provide lyrics for the composed melodies. Persons other than the abatimbo may also get involved in composing songs.

One of the entimbo songs begins by praising the king. It says ‘Orubata n’ekalamu [You travel with the pen]. This was sung to illustrate the fact that King Tito Winyi was literate unlike his predecessors. It adds ‘Orubata nenkuba mukama wangë [You travel with thunder] to emphasize that the same king traveled in an aeroplane, unlike his predecessors. Later the Omutimbo tells a story of how the first Babito king, Rukidi waged war. The singer seems to be telling the former king, Winyi, about the different battles when he says: ‘Let me tell you Adyeri [pet name of King Winyi] how Rukidi fought.’ Then the singer tells the following story:

Solo: When he decided to wage war,

Chorus: he prepared the whole night.

Solo: When King Rukidi went to war,

Chorus: he found them ready.

Solo: He said, ‘You Banyoro should be obedient,’

Chorus: go for battles.

Solo: The Bahuma [aristocrats] blow the battle horns,

Chorus: and go to plunder cattle.

Solo: The Bairu [peasants] hold your spears,

Chorus: and get ready to fight.

Solo: He fought for the Rwebuga drum,

Chorus: while at Bunyamwanga.

Solo: From Bunyamwanga,

Chorus: he spent a night at Bunyamaiswa.

Solo: From Bunyamaiswa,

Chorus: he spent a night at Baramwiire.

Solo: From Baramwiire,

Chorus: he settled at Muduuma.

Solo: The king settled at Muduuma,

Chorus: the chiefs were appointed.

DRUMS SOUNDS

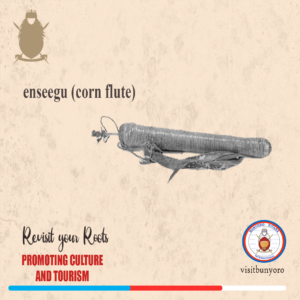

ENSEEGU

The enseegu music was played on wind instruments called enseegu, which were cone-flutes. I first heard the enseegu music from the Wachsmann recordings. I never heard it in the palace, since there were no enseegu instruments there. Okwiiri Kasaija, the official brother of the king (interview, Hoima, 12 June 2009), argued that the enseegu disappeared because each player (omuseegu, plural: abaseegu) kept his own instrument slung around his neck, and upon death no one brought them to the palace for safe custody.

The abaseegu died without passing on the playing techniques to their children probably because when the kingdoms were abolished they did not expect them to be restored again, and might not have felt the need to preserve the instruments and their music. The king (interview, Hoima, 15 June 2009) told me that, like many people of Bunyoro, he did not expect kingdoms to be revived. It seems that no one knows how to play the enseegu today, and few people in Bunyoro remember the structure of the enseegu instrument. During my fieldwork in 2009, each respondent who claimed to have known the enseegu instrument described it differently, and it was even difficult to tell what the instrument looked like. However, I was able to verify and confirm information about it from Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 344-5, 361), and the photograph of enseegu players (Figure 3) that was taken by Wachsmann (1954) and deposited at the British Library. The writings of Wachsmann about musical instruments, especially in Trowel and Wachsmann (1953), are useful because they supplement his recordings.

The enseegu were important royal instruments, and their players occupied a high position in the palace. Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 345) state that they occupied ‘a privileged position at the courts.’ Lenard Kitalibara, custodian of the royal drums (interview, Hoima, 28 May 2009), admitted that he could not move closer to the abaseegu because they were of a very high social status. According to my respondents, the enseegu music was played every day (together with the entimbo music) at the king’s bedroom window to soothe him to sleep and to wake him up. This music also accompanied the king during royal processions.

Yairo Isaliza and Isingoma (interview, Hoima, 12 June 2009) asserted that the abaseegu played other roles as they performed on their instruments. They praised the king ironically, as if to insult him. Isaliza argued that the purpose was to make the king laugh. Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 345) acknowledge this when they refer to Omuseegu as a court jester. According to Isaliza, jests included the following:

Kirole nkokukihurubaire! [Behold how gloomy he is!]

Ebitama byakyo mbe! [Look at his big cheeks!]

Kikurora ebiroliroli nkekitakurora! [Stares like a blind person!]

Kirole ebitiwa byakyo! [Behold his ugly lips!]

Kihurubaire nkebisisi bitafumuirwe!

[He is wearing a gloomy face like those of gourds!]

However, when the king smiled a bit, they would then praise him positively:

Keere nkyanungi! [May you laugh, the good lord!]

Keere agutamba! [May you laugh, Lord!]

Keere rukirabasaija! [May you laugh, the greatest among man!]

Carlson (1993: 318) states: ‘A court jester (omusegu), according to my informants, had the license to joke about the king and use foul language.’ This relationship between the king and the performer also makes Wachsmann and Kay (1971: 408) wonder ‘Why is it that the praise singer so often is utterly abject in his praise of his lord, debases himself, and yet still retains so much freedom of expression and criticism and is sometimes quite wealthy?’ Nevadomsky (1984: 48) also acknowledges how musicians reprimand VIPs in Benin: ‘As they danced ekasa the groups sang original compositions that stated a moral, praised the most deserving, and often expressed open secrets and chastised those of high rank but dubious integrity.’ According to my respondents, the abaseegu made serious points and the king might adjust his behaviour accordingly. Respondents agreed that the abaseegu could say anything before the king and would not be punished but instead rewarded, sometimes with a bull. They were useful in pointing out what the king had failed to do or the scandal he might have caused. On hearing their claims the king would offer them a bull so that they move away from his presence. My respondents asserted that, nevertheless, the king would also ponder on the delivered message and take corrective action. The abaseegu’s words were just spoken and not sung. An example of messages included the following:

Ofadadaire aho, tokuhuliriza ebyabantu bakugamba! [You have parked yourself there, without taking note of what the people are saying!]

Omukama koima! [You are a tight-fisted king!]

Koli mufu! [You are dead—You are a tight-fisted king!]

Ebinyindo bikucuncumuka omwiika! [Your nose is steaming with smoke]

Therefore, I suggest that the abaseegu regulated the king’s actions since people usually took advantage of their status to communicate to the king his weaknesses so that he might adjust. In this way, the abaseegu acted as an administrative tool for reprimanding the king and bringing about royal order, by indirectly controlling the king’s power. In centralised societies where the king has absolute power, it is hard to reprimand him when necessary. However, music provides systems of addressing people who are untouchable.

The enseegu music has not yet been revived although there are possibilities for doing so. It is not clear whether the kingdom officials are keen to revive the enseegu music. Bunyoro kingdom officials usually claim that the kingdom has no funds to restore fully its traditions. It may be argued that it is no longer fashionable and not necessary today to soothe the king to sleep and wake him up in the morning using the enseegu as was done before the abolition. However, it might be argued that the enseegu would be necessary to join other instruments and accompany the king during processions as it was done in the past. I still believe that it is possible to make the enseegu instrument and play its music using the Wachsmann recordings and information from Trowel and Wachsmann (1953: 345). The recordings and Figure 3 would provide the timbre and the style of playing, while Trowel and Wachsmann would provide information about making the instrument. Thus a potentially significant means for communication might be

Enseegu Songs

ENGWAARA

The engwaara songs were played outside the palace on side-blown trumpets called engwaara. According to Yairo Isaliza and Muhamadi Isingoma, the leaders of the trumpet players of Bugambe, Hoima (interview, Hoima, 12 June 2009), the type of songs played on these instruments determines whether the trumpets are amakondere or engwaara, as there are no physical differences between the instruments. When I listened to the Wachsmann recordings of engwaara such as ‘Mulime bajokole’ [You should plant plantains], ‘Abagenyi baizire’ [Visitors have come], ‘Bigambo biri kweba [You will forget issues] and ‘Wambala byomd [a person who is decorated with ornaments], I noted that the engwaara songs were faster than the amakondere songs, and accompanied a faster dance in which men wear gourd-rattles called ebinyege [leg rattles]. Through listening to the recordings one may learn how to hocket the engwaara.

ENGWAARA SONGS

ENGOMA

Roles of Engoma(Drums) in Bunyoro-Kitara.

1. Coronation of Omukama

2. Kwarura abarongo/mahasa(Twins), Twin birth celebration

3. Kweranga – Introduction

4. Kubandwa – Spiritual possession ceremonies

5. Death announcement

6. Communication. e.g Mobilize people for an event

7. Broadcasters – Village carriers

8. Entertainment. Runyege, entogoro